The Journey

WINDRUSH 75

Explore. Discover. Connect

Videos on NLJ’s Youtube Channel

Service Commemorating the 75th Anniversary of the Departure of HMT Empire Windrush

Phillips, Mike and Trevor Phillips. Windrush: the irresistible rise of multi-racial Britain. London: HarperCollins, 1998. 305.896041 Phi

Onyekachi Wambu. Empire Windrush: fifty years of writing about Black Britain. London: Phoenix, 1999.

820.8089641 Emp

Riots, rebellions and revolutions: making freedom: an exhibition marking the 175th anniversary of the 1838 emancipation of nearly a million Africans in the Caribbean. London:

Windrush Foundation and Heritage Lottery Fund, [2013]. Pam 972.9, WI Rio

Levy, Andrea. Every light in the house burnin’. London:

Headline Review, 2004. 823.914 Lev

Cobbinah, Angela and Arthur Torrington. John Richards ‘No Regrets’.

Imperial War Museum London. From War to Windrush. Institute of Jamaica.

Holder, Lorna. Living under one roof: memories from Hackney’s Windrush generation. London: Hackney Museum. PRO000550

Service of praise and thanksgiving in commemoration of the the 56th anniversary of Independence and in recognition of the 70th anniversary of the arrival of the S.S Empire Windrush. 2018 PRO0007794

Geraldine Connor Foundation. Sorrel & black cake: a Windrush story. PRO0007746

National Library of Jamaica. Windrush chronology. PRO0007941

SS Empire WindRush : A tribute to 492 passengers

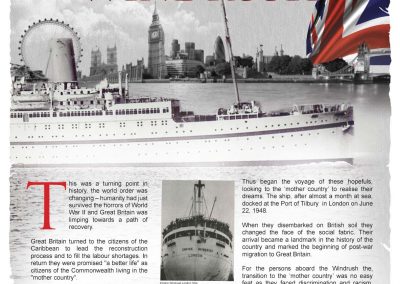

This was a turning point in history, the world order was changing – humanity had just survived the horrors of World War II and Great Britain was limping itself on a path of recovery.

Great Britain turned to the citizens of the Caribbean to lead the reconstruction process and to fill the labour shortages. In return they were promised “a better life” as citizens of the commonwealth living in the “mother country”.

Job advertisements in newspapers such as The Daily Gleaner promised the realization of that dream, for which the applicants paid £28.10s to travel to Great Britain.

On May 24 1948, the SS Empire Windrush set sail from Kingston, Jamaica with 492 official Caribbean migrants, drawn from Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and Bermuda. The ship carried a number of troops, lower deck passengers and a few stowaways.

Jobs were scarce in Jamaica during that time. The island was still getting back on its feet, recuperating from the onslaught of the 1944 hurricane season.

Thus began the voyage of these hopefuls, and looking to the ‘mother country’ to realize their dreams. The ship, after almost a month at sea, docked at the Port of Tilbury in London on June 22, 1948.

When they disembarked on British soil they were to change the face of the social fabric. Their arrival became a landmark in the history of the country, and marked the beginning of post-war migration to Great Britain.

This is a tribute to the 492 passengers who travelled to the UK on the Empire Windrush.’

For the ‘400 sons of the Empire’ the transition to the ‘mother country’ was no walk on the bed of roses as they faced discrimination and racism. Initially sent across Great Britain as labourers, these West Indian migrants overcame the aggression against them and soon made their mark as contributors to industry, small business owners and icons of music and culture. They strengthened their roots in a multi-cultural society and added their unique flavour in a culturally diverse Britain.

more information at https://nlj.gov.jm/empire-windrush

Videos on NLJ’s Youtube Channel

Service Commemorating the 75th Anniversary of the Departure of HMT Empire Windrush

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gfBW1KzEcng

Phillips, Mike and Trevor Phillips. Windrush: the irresistible rise of multi-racial Britain. London: HarperCollins, 1998. 305.896041 Phi

Onyekachi Wambu. Empire Windrush: fifty years of writing about Black Britain. London: Phoenix, 1999.

820.8089641 Emp

Riots, rebellions and revolutions: making freedom: an exhibition marking the 175th anniversary of the 1838 emancipation of nearly a million Africans in the Caribbean. London:

Windrush Foundation and Heritage Lottery Fund, [2013]. Pam 972.9, WI Rio

Levy, Andrea. Every light in the house burnin’. London:

Headline Review, 2004. 823.914 Lev

Cobbinah, Angela and Arthur Torrington. John Richards ‘No Regrets’.

Imperial War Museum London. From War to Windrush. Institute of Jamaica.

Holder, Lorna. Living under one roof: memories from Hackney’s Windrush generation. London: Hackney Museum. PRO000550

Service of praise and thanksgiving in commemoration of the the 56th anniversary of Independence and in recognition of the 70th anniversary of the arrival of the S.S Empire Windrush. 2018 PRO0007794

Geraldine Connor Foundation. Sorrel & black cake: a Windrush story. PRO0007746

National Library of Jamaica. Windrush chronology. PRO0007941

WindRush 19 xx – Present

Alfonso “Dizzy” Reece

Reece, the son of a silent film pianist, was born in Kingston, Jamaica on the 5th of January 1931. His father was worried as Reece had a habit of doing things like “wander the Kingston streets at night and hang out in the middle of potentially violent labor strikes”.

Reece was sent to Alpha Boys School – a hothouse of Jamaican music talent – where he first discovered his love for the trumpet. His musical skills grew exponentially, which he carried with him to Great Britain.

Reece, like his brothers from the SS Empire Windrush, discovered his transition to England would be wrought with challenges and making a career from music would be the last thing on his mind. Putting his musical aspirations in cold storage, he worked as a labourer throughout London before he moved to mainland Europe where he worked much of that time in Paris.

Winning praise from the likes of Miles Davis and Sonny Rollins, the trumpeter emigrated to New York City in 1959 and recorded with several of Davis’ bandmates. However, Reece found New York in the 1960s a struggle.

Reece recorded a series of critically acclaimed records and is still active as a musician and writer. Over the years, he has performed and recorded with the likes of the Paris Reunion Band, tenor saxophonist Dexter Gordon, fellow trumpeter Ted Curson, pianist Duke Jordan, and drummers Philly Joe Jones and Art Taylor.

Reece wrote the music for the 1958 Ealing Studios film “Nowhere to Go”.

Granville Edwards

Granville Edwards, noted jazz saxophonist, was a tall, striking fellow, often described as brimming with style.

Born in Brown’s Town, St. Ann, he was the only boy in a family of seven. His father was a bandmaster, and a source of inspiration for Edwards who gravitated to music.

Edwards, like many young Jamaicans at that time, joined the British Army that was fighting in World War II. Here, his love for music grew exponentially as he got an opportunity to listen to music from other parts of the world on the radio.

When he arrived in England on the SS Windrush, making a living from music was a distant dream. He took up carpentry to eke out a living, but never gave up on his true passion – music.

Edwards lived in various parts of the UK before settling down in Manchester where he resided for almost half a century. He worked in a factory and formed a band – they used to frequently play at clubs, when they grew in popularity.

One of his sidemen was bass player Lord Kitchener, who was better known as a calypso singer. From time to time, jazz musicians from London – notably Tubby Hayes and Joe Harriott – would travel to Manchester and accompany Edwards on his performances.

Edwards also played with gospel singer Sheila Collier, and a fellow Jamaican, pianist Chester Harriott. It was through Harriott’s connection that Edwards got a stint with Granada Television’s Manchester studios.

Edwards continued playing until 1994shortly after the Cork Jazz Festival in Ireland when he was forced to retire because of a blood clot in his lung. Edwards died on August 7, 2004, aged 84.

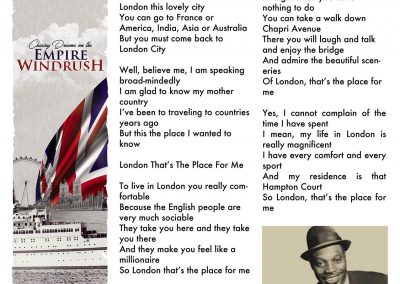

Lord Kitchener

Aldwin Roberts, better known as Lord Kitchener, was born in Arima, Trinidad and Tobago. His father had encouraged him to sing and taught him to play the guitar. His first paying job after becoming a full-time musician was playing guitar for the Water Scheme labourers while they laid pipes in the San Fernando Valley in Trinidad.

He toured Jamaica between 1947-48 with Lord Beginner (Egbert Moore) and Lord Woodbine (Harold Philips) before they embarked on the journey to England aboard the Empire Windrush.

When the ship arrived at the Tilbury Docks, Kitchener performed the specially-written song “London Is the Place for Me”, which he sang live on a report for Pathé News.

In two years he was a regular performer on BBC radio, His popularity soared in the 1950s as he built a large following among the West Indian expatriate communities. Kitchener enjoyed great success in London. He worked tirelessly in clubs, sometimes even performing at three different venues in one night. He composed the infinitely popular Victory Calypso that was the soundtrack to the West Indies Cricket team’s first win over England. Thousands of Caribbean nationals sang the popular refrain “Cricket, Lovely Cricket” and it became the joyous and exuberant soundtrack for West Indian pride.

Kitchener returned to Trinidad in 1962 where he and the Mighty Sparrow proceeded to dominate the calypso competitions of the sixties and seventies.

For 30 years, Kitchener ran his own calypso tent, Calypso Revue, where he nurtured the talent of many calypsonians – Calypso Rose, David Rudder, Black Stalin and Denyse Plummer among them.

He was diagnosed with bone marrow cancer, and retired in 1999 after producing a final album; Vintage. Kitchener died on February 11, 2000 of a blood infection and kidney failure at the Mount Hope Hospital in Port of Spain.

Lord Woodbine

Harold Adolphus Philips, popularly known as Lord Woodbine, was a Trinidadian calypsonian and music promoter. He is regarded by some as the musical mentor of The Beatles, and has been called the “sixth Beatle”.

Born in Laventille, Trinidad and Tobago, in 1943, he joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) and went back to the island after World War II in 1947. He returned to England on the Empire Windrush. His calypso band, Lord Woodbine and his Trinidadians, was one of the first to tour England.

Philips had a variety of jobs in the 1950s such as builder, bar tender and calypso singer, eventually opening his own “New Colony Club” in Liverpool. Philips was a promoter of The Beatles in their teenage years, then known as the Silver Beetles, who frequently played at the Jacaranda Club. The nascent band was occasionally known as “Woodbine’s Boys” due to their close relationship.

The Beatles played at a new venue, the New Cabaret Artists’ Club, that Philips and entrepreneur Allan Williams opened in 1960. Philips helped with their first visit to Hamburg in that same year where he performed as Lord Woodbine on the same stage as the Beatles at their first performance in Hamburg in August .

Philips married Helen (Ena) Agoro in 1949, the couple tragically died in a fire that engulfed their home in Toxteth, Liverpool in July 2000.

Sam King

Sam ‘Beaver’ King was born in Portland, Jamaica and had nine siblings. He initially worked on the family farm before he decided, when he was 18 years-old, to join the Royal Air Force (RAF) in World War II. It is said that he believed if Germany were to win the war, slavery will be re-introduced to the West Indian colonies.

He served as an engineer at Fire Station RAF Hawking and he returned to Jamaica after completing his tour of duty.

King worked for the Royal Mail, and later in his life was a co-founder for what is now known as the Notting Hill Carnival – he was a successful lawmaker and was elected Mayor for the London Borough of Southwark in 1983.

King was passionate about Great Britain and wanted to make every effort to re-build the country post World War II.

“I came with my own directive, if someone want to leave, let them leave, but I have been here during the war fighting Nazi Germany and I came back and help build Britain,” he once told BBC.

King and his friend Arthur Torrington established the Windrush Foundation in 1995. The objective of the Foundation is to preserve the memories of the West Indian migrants who helped to rebuild post-war Britain

King was awarded a MBE in 1998, which was also the year of the 40th anniversary of the SS Windrush’s first docking.

His campaigned relentlessly for the observance of ‘Windrush Day’.

King passed away on June 17, 2016.

After the loss of his friend, Arthur Torrington released a statement reading: “Sam was a giant with a voice that commanded respect that provided a positive message to all about the contribution of the Caribbean community but the wider benefits of migration. We need to give our gratitude to men and women like Sam who made sacrifices and laid the foundations that we take for granted today in the community.”

Cecil Baugh

Cecil Baugh was born in Bangor Ridge, Portland in about 1909 and attended the Bangor Ridge Primary School.

In 1941, Baugh enlisted in the Royal Engineers of the British Army and from his service he gained exposure to different pottery styles. Baugh said he was inspired when he saw the use of Persian Blue colour on one of his deployments in Cairo, Egypt. This colour was similar to one he achieved when mixed copper oxide and glass and the discovery of Persian Blue was very encouraging as he continued to hone his work in ceramics.

Cecil wanted to know everything there was to know about ceramics to enhance his teaching skills on his return to Jamaica. Baugh, though, was not satisfied with the extent of his knowledge, and wanted to go to England.

In 1948, he paid for his passage, sailing aboard the Empire Windrush. Among his goals was securing internship with the famed Bernadrd Leach, who was regarded as the “Father of British Studio Pottery”. Unable to immediately achieve this, he first spent three months working with Margaret Leach, in Monmouthshire. He managed to obtain a one-year fellowship under the guidance of Bernard Leach and by 1949, he was demonstrating on BBC television the walk around technique of traditional Jamaican pottery.

Baugh returned to Jamaica in 1949 and in 1950 mounted his first one-man exhibition.

Soon he, along with Albert Huie, Linden Leslie, Jerry Isaacs and Edna Manley formed the Jamaica School of Art. Cecil Baugh was the last to leave the institution when he retired in 1975.

Cecil Baugh died June 28, 2005 at the age of ninety-six.

Alford Gardner

Alford Gardner, born January 27, 1926 in St. James, Jamaica was 17, when he joined the Royal Air Force RAF in 1944 during World War II. Gardner worked as an engineer and a motor mechanic. After completing his first assignment in Gloucestershire, he received a six-month engineering vocational training.

When the call for Empire Windrush was first announced, Gardner and his brother were among the first to book their tickets.

They embarked on this journey of hope and better life, but when they arrived in London, they experienced the same travails as many of their fellow West Indians, primarily with finding accommodations and employment.

After three weeks of arduous searching, Gardner’s RAF experience and vocational training finally paid off, he got a job at Commercial Engineers Company in Leeds. This was to become his chosen career path, Gardner worked in the engineering industry until his early retirement in 1981 at the age of 55.

Apart from his worldly pursuits, Gardner was an avid cricket lover and is known in the UK as the founder of “The Caribbean Cricket Club” in Leeds.

The club, like the Windrush’s historic voyage, is celebrating its 70th anniversary this year.

JOHN MITCHELL RICHARDS

Born in the Fair Prospect Windsor District of Portland in April 1926, John Mitchell Richards was from the Upper Fair Prospect Windsor Forest and attended the Fair Prospect School with Sam King.

Richards was 22, when he set sail for England on the Empire Windrush in May 1948.

Coming to England, armed with dreams and aspirations for a better future began with a shaky start. When he arrived in the UK he did not find any accommodation and had to move to temporary lodgings at the Clapham South Deep Shelter with over two hundred and fifty other West Indians.

He finally found a job at state-owned British Rail as an undercarriage fitter.

Richards was a part of a workforce who were integral in rebuilding United Kingdom after World War II. The railways was to grow into a key means of passenger and freight transport.

Richards worked for 30 years at British Rail’s Orpington, Kent depot, until he retired at 65.

He, like fellow Windrush traveller Gardner, loves cricket, he was an ardent cricket player and fan and attended cricket matches over the the weekends.

Richards worked hard and build a home for him and his family, in the process realising the dreams that he came to England with.

Richards is now 93, but he is young at heart, and still continues to meet and spend time with his friends and fellow travellers of the Windrush. The annual meetings of this Windrush group are held at Clapham at Kendall Rise Club in Willesden, in the Borough of Brent.

more information at https://nlj.gov.jm/empire-windrush

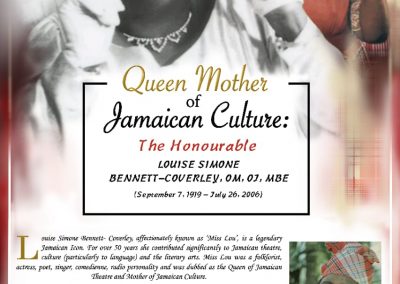

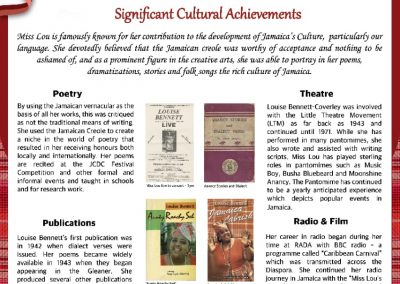

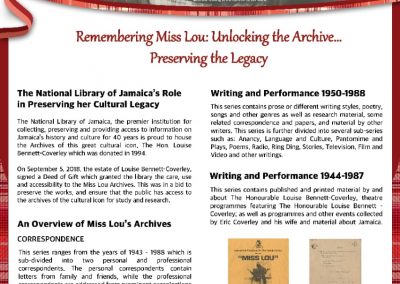

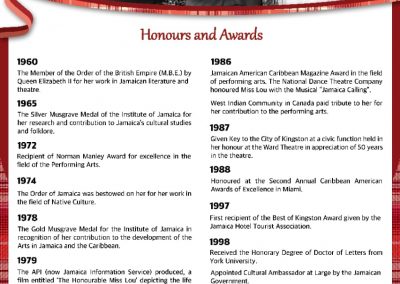

Miss Lou – Unlocking the archives

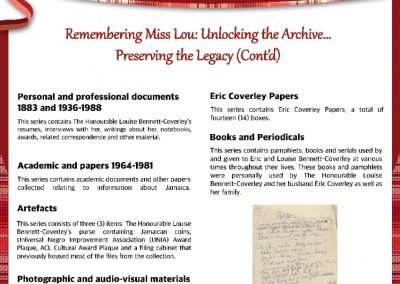

Artefacts, Academic & Papers 1964-1981, Books & Periodicals, Personal & Professional documents

Louise Bennett-Coverley – Miss Lou

Miss Lou’s archive, Legal and Financial, Writing and Performances 1944 – 1988